“When the people are faced with the danger of tyranny they choose either chains or guns”

The further we move away from workers’ revolutions and uprisings, which according to the dominant narrative have definitively passed away as defeated, the more publications about them increase. Why? The past is not a dead field of events. Its view does not remain unchanged. The historical past is rewritten and changed according to the new questions posed by the evolving present. Collective memory is shaped again and again, from the old to the new generations, through an undeclared and endless war. The search for new interpretations concerns both opposing class camps. For the events of December 1944, the alliance of the Greek bourgeoisie and the British had to create a narrative that would justify the slaughter of the communists who fought the Nazis and the famine, trying to establish a free Greece. Years of distortion of historical memory have passed alongside the violent suppression of thought. So that the new generation adapt and accept what the rulers wrote.

December 1944 is not simply a difficult past, which because it challenged the bourgeoisie and imperialism must be erased or undermined in the collective historical memory. The revolutions that were defeated have not ceased to invade the field of real possibility. In other words, they proved that they can happen again.

80 years ago, in December 1944 a battle between British troops and Greek Communist resistance fighters took place in Athens. It was a popular uprising with a distinct class-based character. Citizens, mainly from the poor districts of Athens took up arms and fought against a well-organized army of British and Greek bourgeois forces. While chronologically falling within the context of World War II, which had not yet ended, politically, this intervention was more in line with the Cold War, which had not yet begun.

From Resistance to Liberation

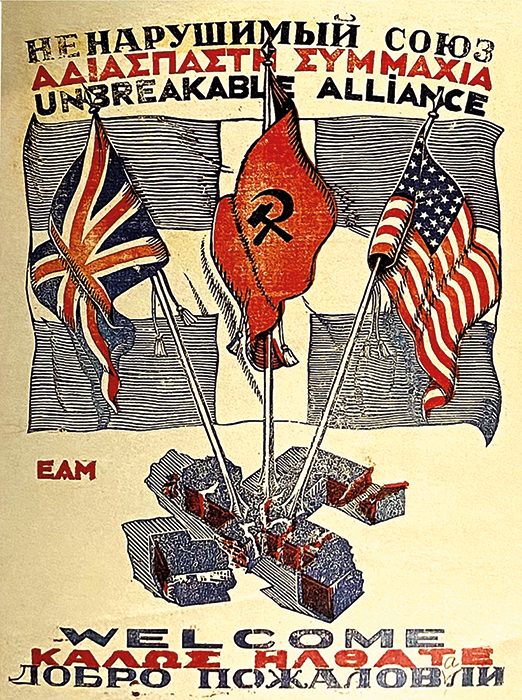

During the Nazi Occupation, the National Liberation Front (EAM), which was founded on the initiative of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), was the largest resistance organization, representing the political radicalization of a significant portion of Greek society. A rift began to form between those who took advantage of the Occupation to get rich and those who suffered because of it. The chasm widened with the outbreak of the deadly famine in the winter of 1941–1942. The worst European famine of World War II, it left at least 45,000 dead in Athens and about 250,000 in total in a country of 7.3 million inhabitants. Most of the victims belonged to vulnerable population groups in urban centers. The largest of these were refugees (about 20% of the population) who had arrived in the country after the defeat of the Greek army in the Greco-Turkish war (1919–1922). In 1941, they still lived in squalid conditions in slums on the outskirts of Athens. These population groups joined resistance organizations en masse, while through its action during the Occupation, the KKE and EAM had managed to acquire members and followers in every corner of the country as well as an important military force, ELAS, which had established his authority over three quarters of the country. Refugees, women, and youth who until then had been living on the political margins found themselves at the vanguard of political action through their membership in EAM. The English leadership, confirming the political (EAM) and military (ELAS) supremacy of the resistance movement in the main part of Greece, became seriously worried and the Greek question began to become an obsessive idea. From September 1943 the British government was considering sending military forces to Greece, not to fight the Germans but to enforce “law and order”. The same concerns were expressed by almost the whole of the bourgeois political world that united around England – even the pro-German and pro-Nazi elements, in order to prevent EAM/ELAS from prevailing in Greece.

From Liberation to a class-based Uprising

On Thursday, October 12, while the Germans were leaving in the early hours of the morning, a large number of people began to flock from the districts of Athens to the city center. When Greece was liberated, three powerful groups were in a position to shape Greece’s future: EAM, the liberals and monarchists who had formed a temporary anti-EAM alliance, and the British. A National Unity government was formed in September 1944, incorporating parties from across the political spectrum including, for the first time, the Communists. EAM was given six ministries. The government arrived in Athens on 18 October 1944 and would serve as an interim authority to carry out the transition from occupied to post-war Greece. The British wanted a friendly government and for the king to return to the throne, since he was the main guardian of their interests in Greece. The British hoped to secure control of maritime routes in the southeastern Mediterranean, through which they communicated with their colonies in India. Moreover, large British companies were active in Greece, mainly in the energy, transport, and construction sectors, while British banks had a significant number of Greek government bonds in their portfolios.

The people celebrating on October 12, 1944 in Athens did not know that Churchill and Stalin had just concluded a negotiation for the Balkans, which will be implemented very soon in the same streets where the enthusiasm and optimism of the Liberation reign. Churchill in a letter to Eden writes: “Having paid Russia the price for freedom of action in Greece, we must not hesitate to use British forces to support royal Greek government […] I expect an open conflict with the EAM and we should not be afraid of it”. It was precisely to this goal that the new bourgeoisie and the social middle strata that emerged from the hell of the occupation and felt a particular insecurity were aligned, especially for the profits that they had accumulated during the Nazi occupation, by unfair means. With the productive fabric disintegrated, hyperinflation, the transport network destroyed, without foreign aid Athens was in danger of experiencing another winter with famine, similar to that of ’41-’42. It is a landscape where hope and optimism coexisted with deep, unbridgeable social and class polarization.

The British-controlled Bank of Greece, proposed a package of fiscal and monetary policy measures such as the increase in the prices of basic necessities, the limitation of the number of civil servants and their salary, the focus on indirect taxes. Gradually but decisively, using the rather effective blackmail of “if you don’t follow exactly the policy we tell you, we will block aid and you will starve”, the British laid the foundations of the post-war trusteeship regime. The creation of the new drachma which was equal to 50 billion old drachmas, meant that, the pre-war deposits of the small depositors were practically dissipated. This development, combined with the extortion of the British to set very low wages and salaries, as well as the open boycott of the Greek industrialists, with their refusal to open the factories, thus inflating unemployment, brought the reaction of the organized working class. The workers saw that the daily wages were set at levels lower than the Occupation. Throughout the month of November, there are ongoing demonstrations demanding higher wages and food aid, but they are scaled back so as not to create a political problem to the National Unity government. Challenges arose regarding the composition of the new army: how many soldiers would come from EAM and how many from the anti-EAM side?

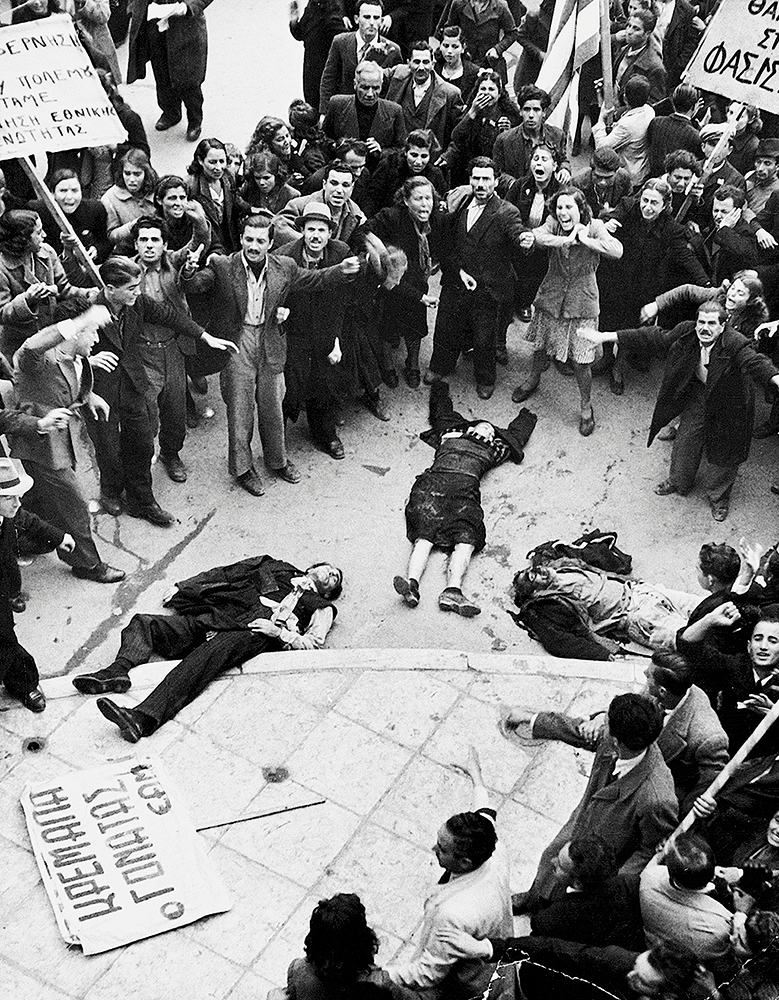

On 1 December 1944, General Ronald Scobie issued a decree demanding the disarmament of the ELAS guerrilla armies. The Prime Minister threatened those who did not comply with criminal charges. EAM could not accept the disarmament of ELAS, which controlled almost all of Greece, without receiving guarantees of equal participation in the new national army. Defying the orders EAM did not hand over its weapons, while mass and militant demonstrations broke out all over Greece against the disarmament of ELAS. The next day, its six ministers resigned from the government in protest. EAM announced a rally in Syntagma Square on 3 December. The government initially gave permission for the rally but a few hours it was revoked. The cabinet decided to order the police to stop the demonstration even with weapons. On December 3, from early in the morning, thousands o f people began to flock to the pre-gatherings, which had been determined in every district of Athens. Soon, the dozens of streams of people converged in a huge sea of people heading towards Syntagma Square. As the head of the march approached the square, the Police forces opened fire on the unarmed crowd. Shots rained down from various directions spreading death. The toll of this attack was 21 dead and 140 wounded.

Even after the massacre in Syntagma Square, a political solution was sought by the British government’s representatives in Athens, the Greek prime minister, and EAM leadership. But Winston Churchill did not accept it. The centrist Greek prime minister handed in his resignation, which was not accepted by the British prime minister, and thus he remained in his post. A general strike strike was declared by the EAM Central Committee for December 4. Its success reached 100%. No factories moved, no shops opened. The people of Athens in a shocking atmosphere of mourning and militancy, accompanied their heroic dead of the previous day to the First Cemetery. When the volume of the funeral procession reached the Syntagma Square, the demonstrators knelt, swore to the memory of the dead. The banner, held by girls in black at the head of the march, read: “When the people are faced with the danger of tyranny, they choose either chains or weapons”. On the way back, a new murderous attack was carried out against the crowd, resulting in the death of 40 and the injury of 70 more fighters. The new murderous attack, one day after the previous one, once again showed the determination of the bourgeoisie to crush the popular movement . The situation would now be resolved militarily. EAM decided to launch an armed response.

The Battle of Athens

During the 33 days of the battles of Athens, ELAS, in the face of the enemy’s overwhelming superiority, had 3,000 rifles, 300 automatic weapons and 500 pistols of all types and types. The first major battle began on 6 December, when ELAS attacked the barracks of the Greek Royal Gendarmerie at the foot of the Acropolis. Some 1,200 young men and women from the refugee municipalities ferociously attacked 550 gendarmerie me inside the barracks. The intervention of the British air force at the crucial moment when the gendarmerie’s defences were beginning to crumble prevented ELAS from seizing the barracks .ELAS’s first operation against a British target took place on 13 December in Kolonaki, a wealthy district of Athens. Guerrillas breached the external wall of the camp where the most important British unit was stationed, entered it, and started fighting hand-to-hand. The British were caught completely by surprise. As soon as dawn broke, ELAS withdrew, taking with them 108 British prisoners and leaving behind 48 British injured and 20 dead.

The mass, active support of EAM – ELAS by the popular masses was the catalyst. The people threw themselves with self-sacrifice and heroism into the battle of the barricades (almost 2,000 barricades were erected in the port of Piraeus alone on December 5-6). In the following days, Athens was a battlefield. Mortars and artillery shells where heard all over the city, British tanks bearded ELAS guerrillas smashing doors and windows to take cover in houses and factories, British airplanes bombing entire districts, and snipers firing from rooftops and bell towers. This was the biggest battle ever to take place in Athens.

The People’s Committees formed an admirable network of recording, gathering and distributing food and other necessities in the districts. Hundreds of sit-ins were organized for the children, the elderly, the refugees of the bombings, etc. Also, as the number of wounded among the combatants and civilians was constantly increasing, dozens of hospital units were organized from the very first days of the fighting, in which hundreds of doctors, nurses and unskilled citizens volunteered to help. Around them stretched a wide and well-organized network of ambulance carriers, who at the risk of their lives and with meager – often improvised – means carried out the task of transporting the injured. Both in the popular mass organizations and in the fighting units of ELAS, many women were distinguished in December, who had already joined the EAM – ELAS en masse since the period of the Occupation.

The fighting can be divided into two phases: before 17 December, when ELAS had the upper hand and the British forces were backed into a defensive posture, and after 17 December, when the arrival of reinforcements gave the upper hand to the British. The self-sacrifice and heroism of the popular fighters temporarily offset the superiority of the opponent’s forces. Indicative of the dynamics of the armed popular movement was the fact that the British were seriously considering even the possibility of withdrawing their forces from Athens, until at least the reinforcements required for the their dominance over ELAS. But London also reacted strongly, ordering Scobie to hold his positions at all costs until the reinforcements that were already on their way arrived .

From December 20, the tide of the conflict began to tilt clearly towards the British forces, with ELAS moving mainly into defensive positions. Churchill informed the USA and the USSR, that he intended to send more British forces to Greece, and they diplomatically agreed.The British counter-attack began on 17 December, after the arrival of reinforcements, organized into 20 infantry battalions, two artillery regiments, four tank regiments with 140 armoured vehicles, and eight air force squadrons with some 120 aircraft. The superiority of the British was overwhelming. At the same time, in the areas the British occupied, hundreds of people were arrested, imprisoned, locked up in camps, tortured, just on the suspicion of their collaboration with the EAM.

On December 24, a special detachment of ELAS transported underground about a ton of dynamite, which it appropriately placed on the foundations of the “Great Britain Hotel” in Syntagma, which functioned as the Headquarters of the British forces. But when it became known that Churchill was coming to Athens and possibly residing in “Great Britain”, the operation was cancelled. Shortly afterwards the British located and removed the explosives. On December 25, 1944, Churchill arrived in Athens. The next day (December 26) a conference was held at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Politicians from all sides of the bourgeois political spectrum, the British Prime and Foreign Minister, the US, French, USSR Ambassadors and EAM – ELAS took part in the conference. The balance had now clearly tilted in favor of the bourgeois side and the outcome of the December battle had been decided. The meeting was organized from a position of power and having an ultimatum towards EAM – ELAS. It is characteristic that on December 27, while the political meeting continued, a general attack by the British forces against ELAS was launched. Finally, after various objections and counterclaims, it was decided to postpone the conference for another day (essentially indefinitely).

Churchill ordered the transfer of a large number of soldiers from northern Italy to Greece. By January 1945, the British government had sent some 70,000 soldiers to Greece, a larger number than it had sent in March 1941 to bolster the Greek defence against the impending German invasion. Churchill gave the green light to major British clearance operations. The major attack against the eastern suburbs of Athens, where ELAS had a significant stronghold, began on 29 December in the municipality of Kaisariani, a slum built to house refugees, that the British called the “Greek Stalingrad”. The British engaged in a fierce two-hour bombardment before the infantry invaded the area. The British attack led to a massacre. In a single day, 290 people died, most of them civilians killed by the bombing. After clearing the eastern suburbs, the British gathered the entirety of their forces for the final strike against ELAS in the city centre, the western and northern suburbs. Some of the fiercest street fighting took place in Exarcheia, where ELAS members, female and male students from the universities were fighting, barricaded themselves in apartment buildings.

Evaluating the developments on the battlefields (the overwhelming superiority of the enemy, the inability to immediately reinforce ELAS and the risk of overspending its forces in the capital), the Central Committee of ELAS issued shortly before midnight on January 4-5, 1945 an order for general contraction towards the mountains outside Athens. Thousands of unarmed citizens, members of mass popular organizations followed ELAS in this march. The retreat of ELAS continued for the next 24 hours under the incessant attacks of the British and especially the air force. Finally, on January 11, an armistice was signed in Athens, by which ELAS was obliged to withdraw from Attica. The battle’s toll reflects its ferocity: 70,000 injured, 5,500 dead, and 25,000 displaced in only one month of fighting.

On 12 February 1945 the Varkiza Agreement was signed between EAM and the Greek government. One of the pact’s major terms was ELAS’s disarmament. Immediately after ELAS surrendered its weapons, the period of “White Terror” (1945–1946) began, a time of relentless persecution of communists by law enforcement agencies and far-right paramilitary groups. This persecution forced many former ELAS guerrillas to take to the mountains again and was one of the causes of the Civil War (1946–1949). The king returned to the country in 1946 with a rigged referendum. Anti-communism became the central state policy. Post-war, the state apparatus was not purged of the collaborators. On the contrary, those who fought against the Communists by cooperating with the German occupiers were employed in post-war governments to build the new state. The nationalist state institutionalized harsh persecution of the communist Left (thousands of executions, long-term imprisonment, and exile). The heroic popular revolutionary struggle in post-war Greece ended in defeat.

Could EAM and ELAS win?

One of the reasons that ELAS did not take advantage of the plight of the British during the first phase of the December Battle was that EAM-KKE decided to prioritize political over military objectives. They attempted to push the British into negotiations by attacking at first only the Greek government forces. This explains why ELAS did not carry out the anticipated general attack against the inadequate British forces in the centre of Athens during the first phase of the battle.

The EAM, despite its contradictions and the agreements it signed, was oriented towards a new social order, which it claimed, rallying around it the popular working majority and representing its class interests in the complex and difficult post-war conditions . That is, in the period when the political line of the Popular Fronts, effective during the occupation, was faced with its impasses and contradictions as the strategy of the opposing side was clearly the recovery and safeguarding of bourgeois power. In the new reality created by the Occupation and Resistance struggle, EAM represented the general demand for political change after the end of the war. The situation in Greece – and especially in the capital, severely tested by hunger– was revolutionary. The experience of occupation and resistance, which now bore the fruit of Liberation, had created a people who, in addition to national liberation, longed for social liberation as well. At the same time, the situation in the Balkans was changing in a way that decisively strengthened the communist forces. Bulgaria had been liberated from the Red Army, which had entered Yugoslavia along with Yugoslav Partisans. Albania was already almost entirely controlled by the Albanian Partisans. In Italy, the growth of the pro-communist partisan movement was significant.

The above does not outline an easy situation. On the contrary, the difficulties were varied and not inconsiderable. But this is a particularly fluid historical moment, where all the elements of what we would say characterize a “historic opportunity” for the revolutionary overthrow of bourgeois power in a country are condensed.

It would be inaccurate to claim that the KKE had not worked out plans to seize power approaching the liberation of Athens. The truth is that these plans never became his main focus. They existed both as a “political platform” within the leadership of the KKE, but also as unfinished plans on paper. The anguished pleas of ELAS guerrilla leaders to allow them to enter Athens is a proof of the existence of this tendency and logic within the party and the revolutionary movement.

However, the leadership of the KKE was not helped by the general political direction that defined the orientation of the communist parties. Starting from 1934, when the stage of the “bourgeois-democratic revolution” enters the documents of the KKE, until the logic of cooperation with the bourgeois and liberal forces in the context of the anti-fascist front introduced a little later, the revolutionary seizure of power is distanced and complicated. Clearly, the rise of fascism and World War II are not simple periods. The Communist International is being tested in unprecedented conditions. The Popular Front tactics bring legitimacy and massiveness, but at the same time they set barriers to the revolutionary emergence of the social issue and the special interests of the working class. The Soviet Union, although it does not bear the main burden for the failed tactics in Greece bears certainly with the responsibility of insufficient policy, international aid to the KKE or even harmful advice. However, the main responsibility must be sought in the KKE itself and its leadership, which failed to adapt to the different conditions of EAM domination in liberated Greece.

At the time of liberation, with the return of the bourgeois forces co-assisted by the British, the ideological confusion of the KKE leadership intensified. It is characteristic that after the decision of the KKE to participate in the government of National Unity, it stands with embarrassment in front of the counterattack of the bourgeois parties. Thus, the KKE – as a national “force of responsibility and normality” and not as a revolutionary party – will back down from its position of equality of ethnic minorities, which contributes to the crisis and rupture with the rebel sections of ELAS in Macedonia , the days when Athens is liberated.

The Yugoslav example shows that strength in the field and boldness can nullify any “agreement”, which in such fluid times can only be taken as a statement of intent. However, within the KKE, the compromise always prevails. Many half-steps do not constitute a complete stride. During the first phase of the liberation, the main role reserved for ELAS was that of maintaining order and guaranteeing normality.

December 1944 in Athens is a typical example of how a deep crisis — one taking the worst possible form, that of war and foreign military occupation — can, in a very limited time, sweep away political constellations, provoking their rearrangement or even their complete overthrow on a national and international level. The Battle of Athens shows that the post-war world had begun. The division of Europe into spheres of influence was the first episode in the coming Cold War. Greece was the only Balkan country to enter the British sphere of influence, with the consent of the Soviet Union.

The Battle of Athens was not a regional conflict concerning a small country in the Balkans. It was part of a broader conflict that broke out within European countries over post-war power. The end of the war marked the beginning of a process of re-establishing state power in a volatile environment that left many possibilities open. The Allies tried to control this process by political means and, where this was not possible, with armed forces.

For the Allies, interested in stabilizing power, preventing revolutions and uprisings, and securing their interests, the December Uprising in Athens represented the great risk they saw for post-war Europe. They feared that the scenes in Athens might spread throughout Europe. If the December Uprising became a successful example, it could be transmitted, domino-like, to other European capitals.The Soviet leadership saw the possible, as it noted, popular uprisings in the West more as a potential destabilizing factor for its relations with it than as an opportunity to expand the socialist camp. In this sense, the KKE leadership, if not discouraged, was certainly not encouraged to take the next step.

The side of the Greek bourgeoisie and British imperialism was determined from the beginning to take back the power. They did not hesitate to shed blood on the Greek people who were calling for the overthrow of bourgeois power. On the contrary, the side of the working class, led by the KKE, fought the battle ideologically and politically unprepared, with hesitations, vacillations and compromises. Heroism, self-sacrifice and revolutionary instinct were not enough, as programmatic and political determination were lacking, while bourgeois-democratic illusions, national unity, were in excess. The revolutionary conflict of December, the heroic battle of the communists and the people of Athens is our heritage. However, honorific mention of the revolutions of the past is not enough. December 1944 reflects the existence of the revolution possibilities and not the illusions about them.